Funny Business: part 4 of a series On Conservative Aesthetics

Book review: Comedic Nightmare by Marcel Danesi

Donald Trump disarms the media, including the comedy establishment, with his buffoonery. In the run-up to the 2024 election, the media, comedians and late-night talk show hosts doubled down on their mockery to try to keep him out of office and failed miserably.

What is it about Donald Trump that is so impervious to criticism, so ineffable?

Marcel Danesi wrestles with this question in his book Comedic Nightmare: The Trump Effect on American Comedy.1 Published in 2022, the book describes the impact of Trump’s 2016-2020 first term on American comedy, breathing a sigh of relief that he was not re-elected in 2020 but never anticipating that there might be a second term. Trump’s second term is shaping up to be very different than his first, so timing is one limitation of the book.

Comedic Nightmare is accessible, not burdened with academic theory or obscure, specialized terms. It is focussed on popular culture, bringing up many names that will be familiar to readers. This illustrates how strong the tradition of comedy is in America. If you are interested in reading more about humour in America, it is well-referenced.

Danesi is trying to understand Donald Trump’s character by examining the many sides and characters of comedy, from Commedia dell’arte to vaudeville to sitcoms and standup. He shows how American comedy has evolved and considers how Donald Trump fits into this evolution, playing the fool or clowning around to manipulate his audience while creating a circus-like spectacle that entertains while distracting us from serious issues.

Donald Trump’s antics have undoubtedly impacted comedy as both a participating comic actor and in provoking comedians and others to react, whether to cope or criticize.

The sad clown face arc of American comedy

America has a strong tradition of comedy that Professor Danesi describes as “playful” and “wry, witty and innocent, free of political harangues and ideological antagonisms.” He gives many examples, including George Burns and Gracie Allen, Abbott and Costello, Laurel and Hardy, the Marx Brothers, and the Three Stooges, tracing their acts back to vaudeville.

Danesi argues that American comedy, as it emerged from the vaudevillian tradition, could never be characterized as “dark.” Rarely, if ever, did it touch on taboo subjects or things that might be considered serious or painful.

He goes on to trace the emergence of darker comedy in the 60s with comics like Lenny Bruce but then skips ahead to Bill Mayer, what seems like a thousand years later (actually about 50). This is fine. He is making the point that there has been a seismic change in the tone of comedy since Donald Trump came onto the stage.

But there is a dark underbelly of standup comedy that seems overlooked in Danesi’s book. There are so many comics, from George Carlin and Robin Williams to Louis CK and Dave Chappelle, whose private stadium shows are ribald and often scandalous, sometimes dark. Standup is an entire industry built on indiscretion, darkness. (If you look up “standup” on Wikipedia, you will learn that from the 1930s to the 1950s, comedy clubs in the U.S. were operated by the mafia.) Danesi’s claim that American comedy has been all happy-go-lucky until the golem arrived needs qualification.

But through the Trump era, Danesi argues, comedy did not just become obsessed with Trump’s antics; it fundamentally changed, becoming polarized, angry and bitter as a result of what he calls “The Trump Effect.”

I think it would be more fair to say that polarization had been growing since the 1980s when identity politics took root in America (and Canada btw), and the griping and finger-pointing reached critical mass around 2010, leading to Trump’s election in 2016.

Danesi fears that Trump has left an indelible stain on American comedy, but it could as easily be argued that the darkness has been there in the wings all along and that he has merely dragged it into the spotlight, in part by claiming to be the antidote.

American satirical tradition

Danesi traces subversive comedic writing in America as far back as 1637 when Thomas Morton skewered “the priggish fabric of colonial America.” His book was so disruptive, it was one of the first to be banned in America.

Writers like Nathanial Hawthorne and Mark Twain followed, critically parodying controlling forms of government and social behaviour. Their work was continued by figures like Will Rogers and W.C. Fields, building a tradition of independent, critical thinking.

Vaudeville started in America in the 1800s, growing in popularity through to the 1930s. It combined all kinds of entertainment, singing, dancing, circus arts, theatrical recitation and skits. Two kinds of comedy emerged from vaudeville: slapstick and the monologue, which evolved over time: slapstick into cartoons and sitcom, and monologue into standup.

Danesi spends considerable time discussing Archie Bunker, the creation of Norman Lear, played brilliantly by actor Carrol O’Conner, in the sitcom All in the Family (1971-79). It was groundbreaking and very popular and, Danesi argues, the beginning of polarization in the comedy sphere. Archie was a working-class conservative, a bigoted sexist railing against the liberalization happening all around him.

There is an obvious connection between Archie Bunker and Donald Trump but it is a flimsy one. They are both blunt, judgemental and unapologetic. But Donald Trump is neither racist nor sexist, at least not overtly. He is, rather, a contrarian, someone who swims against the current, whatever it is. And he is anything but your average type of blue-collar guy. He is arrogant and stubborn beyond estimation. He wants to stand out. This could hardly be said about Archie, who was fundamentally unempowered, harmless, rarely moving from his reclining chair in front of the TV at home.

Nevertheless, the media loved to compare Donald Trump to Archie Bunker, decrying his scandalously semi-literate take on everything from social relations to the environment. If anything, Donald Trump learned from the comparison, cultivating a course public persona that could call things out however he wanted, guaranteed to make headlines.

Conclusion - an arrow that falls short of the target

As interesting as Professor Danesi’s book is, it fails to find chinks in Donald Trump’s armour through which the pointed arrows of comedic truth-telling might pierce.

Danesi considers whether the comedic assault on Trump before the 2020 election contributed to his losing that election but cannot say definitively whether it had any impact. This is understandable: Nobody polls audiences about their voting preferences before and after an episode of Stephen Colbert’s show. The very idea that comedy, even when seen by millions, can be consciously used to affect political allegiances is an example of how the liberal establishment thinks of culture as leading rather than reflecting and contrives to make culture serve ideological ends.

Professor Danesi notes that the foundation of American humour lay in reaction to prudery, the “Protestant work ethic,” with its humourless drudgery and miserliness. Remnants of that type of rebelliousness can be seen in American sitcoms, movies and standup, whenever the joke pivots on a character out-of-step with their times. But this “old-fashioned” type is a vanishing breed. If comedy has changed, maybe it is because there are no old-fashioned people in a world where everyone has a cell phone.

Moreover, the basics of business have changed in the post-WW2 era. Donald Trump has identified himself as a “businessman.” This has scrambled the minds of critics who are embedded in the bureaucratic, technocratic apparatus but whose work is supported by a capitalist system. Capitalism makes it possible for them to pose as humanist and socialist critics, a duplicitousness that has been rudely laid bare by people like Donald Trump.

Furthermore, American entrepreneurialism has raised profit to the status of a virtue, and profit is not an easy target for humour. Unlike the traditional “virtues” of frugality, diligence, temperance and industriousness, profit lacks the stodginess of the Puritans, and most people respect it when not envious.

Entrepreneurs themselves are not good targets for humour either. Unlike the industrialists of the 19th and 20th centuries, today’s businessmen enjoy unprecedented freedom in where and how they work. They marshal resources to create ‘startups’ in diverse, often illusive, ways, and their businesses are decentralized and technologically complex. “Workers,” known as such in industrial times, no longer exist as such, having been replaced with tradesmen and bureaucrats who enjoy middle-class lifestyles and “gig” workers or “digital nomads” whose “means” are hard to fathom.

The classic binary, “oppressor” and “oppressed” does not exist, or at least not in familiar stereotypical ways that are easily parodied.

Professor Danesi correctly identifies Donald Trump as a “buffoon,” and Commedia dell’arte character, and acknowledges his remarkable ability to perform. He identifies Trump with the Commedia characters Brighella and Pantalone. Brighella is the shrewd liar who always turns things to his favour. Pantalone loves money, goes from emotional extreme to extreme, manipulates people to do his bidding and never forgives an opponent. Sound familiar?

But just as comedians and late-night talk show hosts with their relentless “truth-telling” failed to turn the tide of the 2024 election, so too is this academic critique, however well researched and thought through, doomed to fail.

Who could have imagined that such traits would ever be seen in a world leader, let alone that they might make him virtually unstoppable?

The work ahead

Donald Trump is changing the world. Or perhaps it would be better to say that the world is changing and Donald Trump is part of that change. People are starting to talk in those terms, “end of an era,” and not just political regime change.

However you describe it, popular or populist democracy is rising. The old guard — defined as technocratic, bureaucratic and authoritarian (demanding conformity and compliance) — is waning.

Generally, this is perceived to be a rise in conservatism, though the terms “left” and “right,” like “socialist” and “capitalist,” themselves feel outdated and inadequate to describe what is going on. Certainly, there is a sense of balance shifting.

I think it’s important to understand this shift from a cultural perspective.

Lately, I have been puzzled whether the cultural sphere is intrinsically “social” or “left-leaning” because it involves imagination, creativity, observing and caring about how people think and act. Art and culture are shared. Emotions and empathy are involved. But this is an idea that warrants its own post, for another day. (Sorry)

In any event, it is quite clear that culture in the West has been dominated by lefty- liberal ideology in the “modern” period, the 20th century.2 That used to be rebellious, innovative, creative, sparking change, until it was not. And now we are on the cusp of change.

Funny business

I previously wrote that conservatives are culturally retarded and humourless. That sounds harsh, but I stand by it. I use the term “retarded” in a technical way, like in the case of delay in an engine’s spark plug firing. Conservatives are “behind” in terms of culture, and as a result, conservatism is not well understood or accepted, particularly by people on the left who are “cultural.”

As to their humourlessness, Professor Danesi gives some examples of comedians who “lean right”. But that’s not what I’m getting at. Conservatives are not going to comedy clubs to hear their values attacked or endorsed. Conservatives do not care what lessons are being preached at the local art gallery or movie theatre.

The fact is that Donald Trump, like most conservatives, does not know how to take a joke. Anything that puts him down, even in a comical way, he considers an insult. When he tries to be funny, it always comes off as angry and insulting.

“In the end… Trump out-trumped his comedian attackers… He did this by achieving a kind of “meaning control” over humor (sic). Those who opposed him were perceived as villains...”3

Not all business people lack a sense of humour, but business per se is anything but funny. Even the entertainment “business” of studios, financier/executive producers, directors and managers is notoriously unfunny. This is because humour is not in itself productive. It is a commodity.

Comedy in all its forms is certainly fun and interesting, and quite possibly even healthy, making us happier, more congenial, cooperative and productive as human beings. But it will never be regarded as necessary, unlike business which situates itself next to, and indispensable for, survival.

Dark times beget dark humour, or do they?

Professor Danesi devotes a section to the idea of gallows humour, which he is arguing has taken over comedy in America because of Donald Trump. He admits the form goes back to antiquity, perhaps even being “part of an unconscious archetypal instinct.”4 and tells a funny story about the infamous 19th C murderer William Palmer, reputed to have said when approaching the trap door on the gallows, “Are you sure it’s safe?” [Note to self: there’s a cartoon in this.]

I’m not so sure comedy has been taken over by darkness, also known as black humour. In the run-up to the 2024 election, the media were unrelenting and it is unsurprising that many people, including women, Black and Hispanic voters who were expected to support Harris, were turned off.

It’s not true that there’s no comedy, or only dark comedy, during dark times. I think it was C.S. Lewis who observed that while there is unspeakable suffering during wartime, it also occasions much virtuous action. It may have been Lewis too who said that, contrary to what many people say about evil running amok during times of conflict, faith and God are never more present.

Comedians have to carry on just as the rest of us do. They may view their work as particularly important in tough times when morale needs boosting, and it’s healthy to poke fun at the foibles of politicians and generals or laugh at the absurdity of it all.

Thus, we have and will continue to have comedy clubs and late-night talk show hosts with their diatribes against the golem of Donald Trump, the insanity and inanity of it all. They should not give up, of course. The “public sphere” still exists, notwithstanding the impossibility of coherent consensus at the moment. And a bon mot, a clever repartée, is a joy, if not forever, for now. And that should be enough.

If there is a lesson to learn from Professor Danesi’s book, it is perhaps that the conventional ways of analyzing phenomena like the “Donald Trump Effect” will not get you where you want to go. Innovation is needed; a new form of comedy and critique (truth-telling) that is persuasive in ways we have yet to imagine.

Such innovation may be taking place right now as we speak.

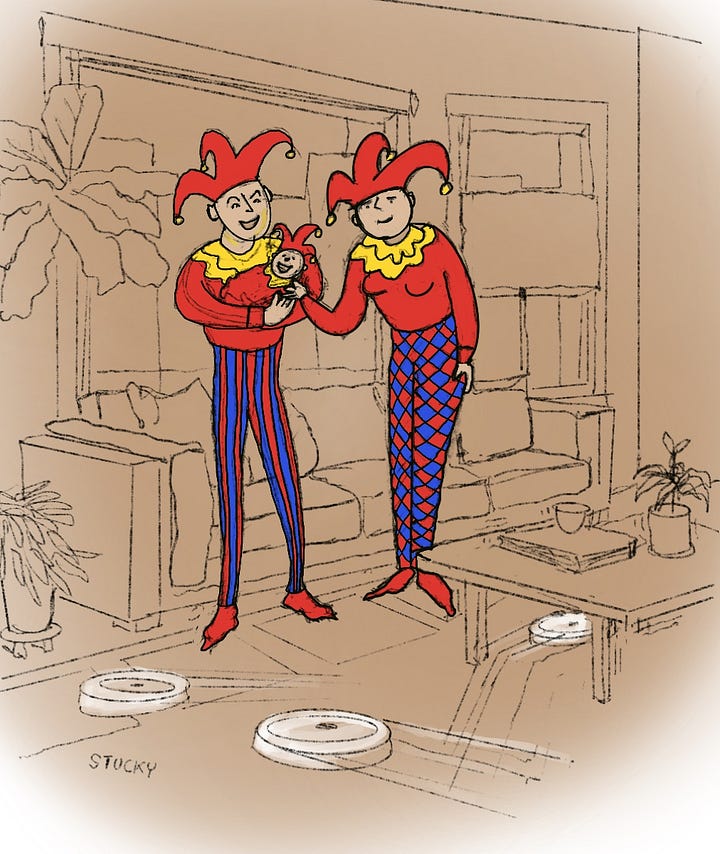

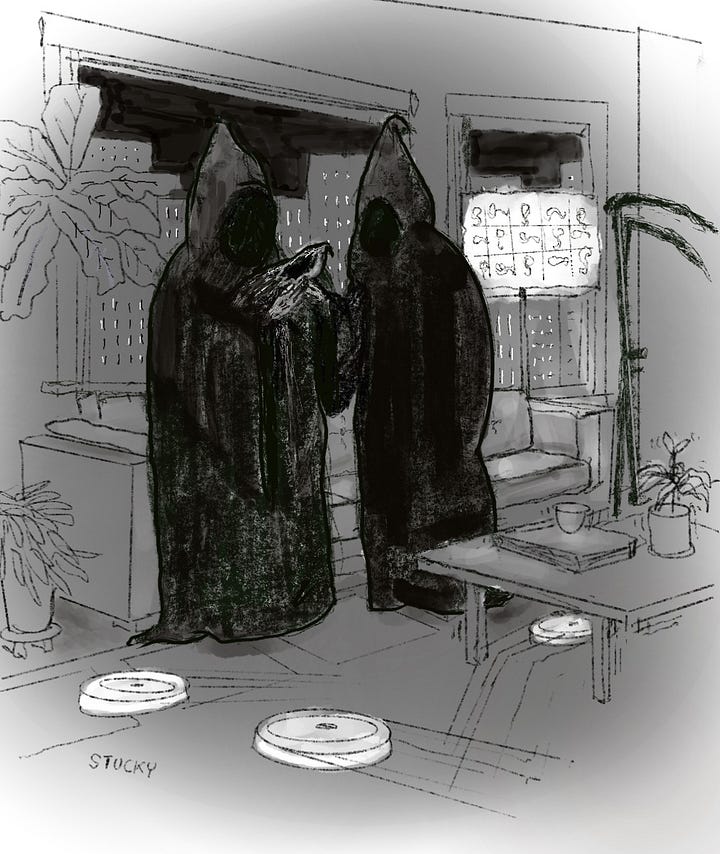

P.S. About the illustrations in this post:

I created a scene, a small-ish NY apartment and then populated it with a young couple with a child. The couple happened to be comedians, or at least one of them is. Hence jesters. But they might have been clowns. Or they might have been the Grim Reaper family.

I don’t know if this series of sketches is dark or just obscure. One of the worst things about comedy and cartooning is the awareness of the audience. You should, as

does with his friend Scott Dooley, ask, Is it funny? But it’s a terrible question to ask and answer if you’re an artist.In any event, I love the idea of one scene having different interpretations. The New Yorker’s caption contest comes to mind: the audience completes the gag by creating the caption.

The cartoon in my post Jan. 6, is a good example. The scene, zombies descending on the Capital in Washington, lends itself to many interpretations. My favourite was and still is the original, “His peeps.” After the 2024 election, though, the caption might well read, “Democrats.” Or, most recently, given where I live, “Canadians.”

This is part 4 in a series of posts about conservatism and culture called On Conservative Aesthetics. Link to the index page for the series here.

Past posts about jesters, clowns and comedy:

Comedic Nightmare: The Trump Effect on American Comedy, Marcel Danesi, Brill, Leiden/Boston, 2022. Marcel Danesi is professor emeritus of the University of Toronto where he taught semiotics and linguistic anthropology. His other publications include The Semiotics of Emoji, the Rise of Visual Language in the Age of the Internet, published in 2016.

I recently came across a Substack post that argued that we are entering a new era, where era is defined as a distinct cultural period of about 125 years. The “modern” period might then be roughly 1885-2010. [citation needed]

p. 66

p. 69

Thanks for this. Interesting. Comedy is essential in all times. I think comedians are the bravest!

"a bon mot, a clever repartée, is a joy, if not forever, for now. And that should be enough"