Part 3A - Conservative Artists

What we can learn about conservative aesthetics from Andrew Wyeth, Norman Rockwell and Thomas Kinkade

If you type “conservative art” into Google, you get a dismal selection of stereotypically traditional paintings. It’s realism from top to bottom; there’s a limited range of styles, some more modernistic or more illustrative, but generally, everything is predictable, sentimental, and technically without distinction. How can conservatives like such terrible art? Or perhaps the question is, Are conservatives doing something with art other than “liking” it?

Let’s examine three well-known American artists. In the next post, Part 3B, I’ll discuss a few more contemporary, meaning living, artists.

Andrew Wyeth

“Wyeth's art has long been controversial. He developed technically beautiful works, had a large following and accrued a considerable fortune as a result. Yet critics, curators and historians have offered conflicting views about the importance of his work. Art historian Robert Rosenblum was asked in 1977 to identify the "most overrated and underrated" artists of the 20th century. He provided one name for both categories: Andrew Wyeth.” - Wikipedia

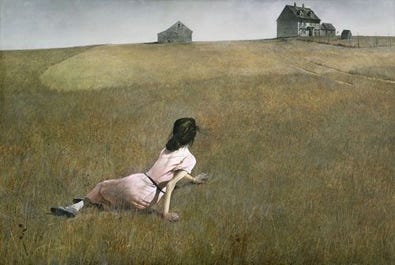

Christina’s World is Wyeth’s most famous work. It is an image familiar to millions of people. It fits comfortably within Wyeth’s oeuvre of paintings of people he knew and places around him. He was regarded as a regionalist in part for this reason, but also because his work did not conform to the trends of modern painting which was, at the time, leaning toward expressionism, loose handling of paint, and abstraction.

Christina’s World garnered more attention than usual, partly because the main figure, Christina Olsen, had health issues. The figure at first glance might appear to be relaxing in the grasses near her home, perhaps responding to a call to dinner, but there is a haunting quality to the image. The angular awkwardness of the figure and her frail arms suggest another reading, of a helpless person far from home, looking to see if someone is coming to help her, will she be heard if she calls out? It’s a poignant moment, filled with tension amplified by the composition: the high horizon, the stolid building far away.1

A precedent for Canada’s Alex Colville?

It might be argued that Wyeth was ahead of his time. Thirty years later, if he had been painting at the same time as Canadian Alex Colville, he would have been considered a postmodern master because of the psychological tension embedded in his images.

Subject matter is one part of Wyeth’s conservatism, and technique is another. Like Colville and many realists, Wyeth's work is painstaking, painted with tiny brushes and tens of thousands of strokes over large areas. Colour harmony and composition are also exacting; the images are constructed like fine furniture.

Norman Rockwell

Rockwell’s Freedom of Speech (shown above) was one of four paintings of freedoms protected in the US. They were painted at the time the US was entering WW2 and used to promote the sale of war bonds. They are especially evangelical you might say, or propagandistic, about American virtues seen to be under threat from the fascism (Hitler and Mussolini) that was overtaking Europe and threatening the world. The president at the time was Theodore Roosevelt, a Republican, a realist and a conservative who deplored idealist liberal themes.

“Norman Rockwell was an American painter and illustrator. His works had a broad popular appeal in the United States for their reflection of the country's culture…. Rockwell produced more than 4,000 original works, including over 300 covers for the Saturday Evening Post and was also commissioned to illustrate more than 40 books and to paint portraits of Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon. … Rockwell's work was dismissed by serious art critics in his lifetime. Many of his works appear overly sweet in the opinion of modern critics,[ especially The Saturday Evening Post covers, which tend toward idealistic or sentimentalized portrayals of American life. This has led to the often deprecatory adjective "Rockwellesque". Consequently, Rockwell is not considered a "serious painter" by some contemporary artists, who regard his work as bourgeois and kitsch. Writer Vladimir Nabokov stated that Rockwell's brilliant technique was put to "banal" use, and wrote in his novel Pnin: "That Dalí is really Norman Rockwell's twin brother kidnaped by gypsies in babyhood." He is called an "illustrator" instead of an artist by some critics, a designation he did not mind, as that was what he called himself. - Wikipedia

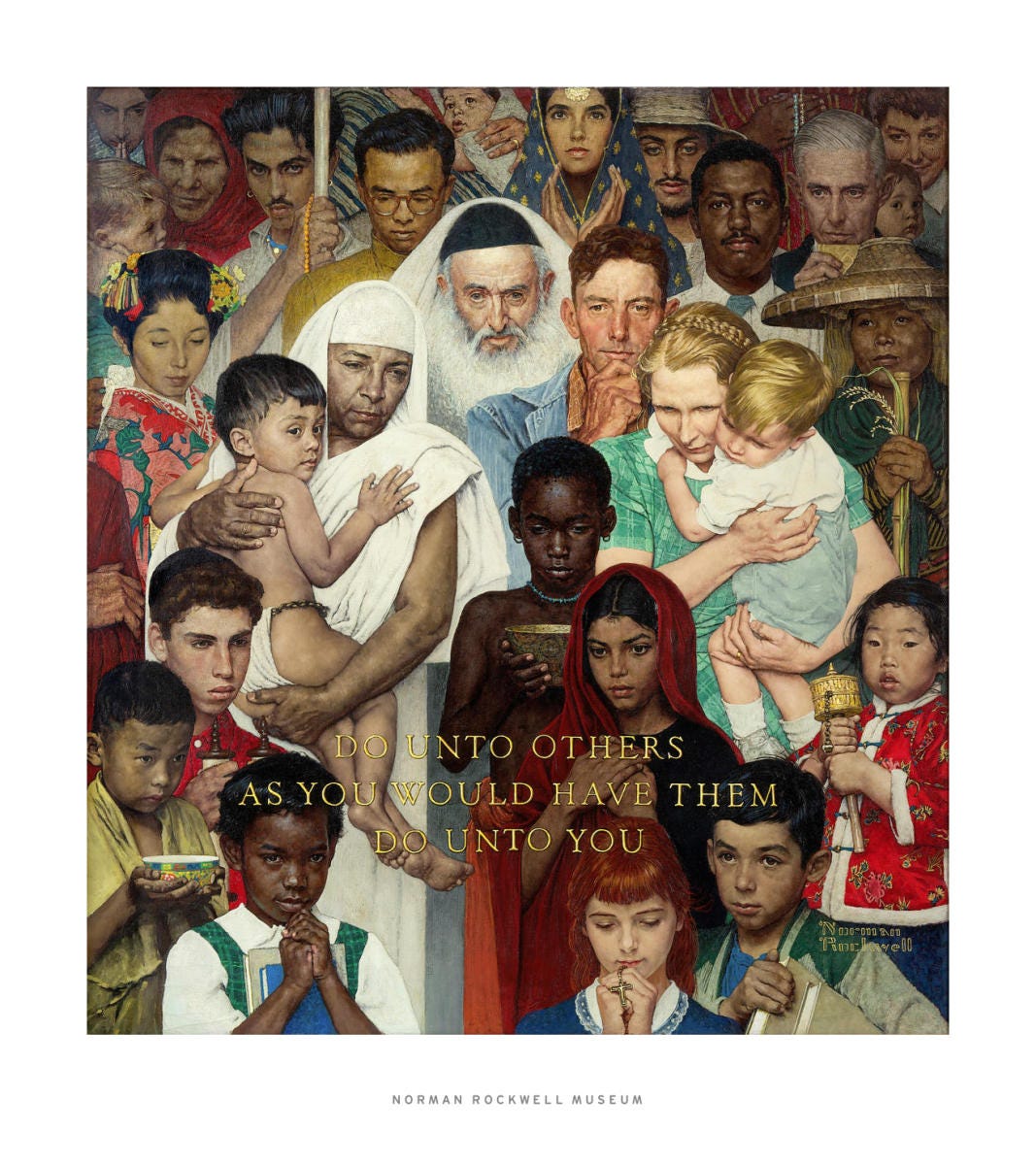

Rockwell’s sentimental pictures of rustic Americana may be considered icons of conservatism. It is thought that Rockwell was probably a Republican voter, and, like many artists of the time (and not only artists, of course), went along with certain prescriptions by magazine editors about race and social status. But it is well known that Rockwell voted for Kennedy in 1960 and never turned back, producing some remarkable advocacy pieces for racial equality, such as the work called The Golden Rule below.

Rockwell painted portraits of both John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon in 1960, but is reported to have said of Nixon, “The problem with doing Nixon is that if you make him look nice, he doesn’t look like Nixon anymore.”

Much has been made of Rockwell’s “conversion” to liberalism. I think that it’s not that complicated. He was a super talented man and the subjects he chose and the way he painted them show that he was a decent sort of guy who loved people and loved his country and the American way of life. It’s reasonable to think that he saw things changing and embraced the change. There is a very good story here about Rockwell’s changes in the 60s.

I don’t want to minimize Rockwell’s convictions or change of heart. The point is, I think, that political convictions are separate from how people create and what they create, or at least they can be. This is one of the deep complications that make the whole idea of a conservative aesthetic problematic. Rockwell’s style did not change in the 1960s. What changed was the subject matter, and then not that much really. A concern for social justice was topical at the time and Rockwell believed in the need for change. He had a knack for catching the zeitgeist, that is until his kind of sentimental realism became passé.

Some formal things about art are associated with conservatism, things like realism, sentimentality, and Americana, as Aaron M. Renn has pointed out (and I discussed in my last post), but the people who make such images may or may not be politically conservative and they may or may not be intentionally directing their work at conservative audiences. Which brings us to:

Thomas Kinkade

Thomas Kinkade was an American painter of popular realistic, pastoral, and idyllic subjects. He is notable for achieving success during his lifetime with the mass marketing of his work as printed reproductions and other licensed products through his own company. According to the company, one in every 20 American homes owned a copy of one of his paintings.

Kinkade described himself as a "Painter of Light", a phrase he protected by trademark.

Kinkade was criticized for some of his behaviour and business practices; art critics faulted his work for being "kitsch". Joan Didion, in her inimitable style, said,

“A Kinkade painting was typically rendered in slightly surreal pastels. It typically featured a cottage or a house of such insistent coziness as to seem actually sinister, suggestive of a trap designed to attract Hansel and Gretel. Every window was lit, to lurid effect, as if the interior of the structure might be on fire.

Kinkade had supporters as well: Mike McGee, director of the CSUF Grand Central Art Center at California State University, Fullerton wrote:

“Looking just at the paintings themselves it is obvious that they are technically competent. Kinkade's genius, however, is in his capacity to identify and fulfill the needs and desires of his target audience...”

- all above from Wikipedia.

I expect Kinkade has many imitators but none have been so successful. Kinkade’s images are expertly rendered but also conceptually extremely consistent. He stays on type and the rest is very effective marketing.

The type is realism, of course, and sentimental, though in a different way than Rockwell. Kinkade’s paintings are invented scenes of Americana, not painted from real life and not trying to imitate reality. They are not exactly fantasy and they are not surreal, but idealistic and hyper-real.

And the appeal of Kinkade’s work is also different than Wyeth’s or Rockwell’s. Wyeth was popular among people who were into the arts. Although his conservatism cut against the grain, there was no shortage of patrons, galleries and museums to support his work. His talent spoke for itself.

The same thing could be said for Rockwell too. Though he found his support through the press, the Saturday Evening Post and other publications, it was a similar audience of art-aware and educated people who valued talent.

Kinkade differs in that his work appeals to a much broader audience, one that might never find itself in a gallery or museum, but that nevertheless had a popular (or populist?) sense that “artistic paintings” might have a place in their homes. Mass production and corresponding prices made his work accessible in a completely different way from Wyeth or Rockwell.

Up where I live, there is an Indigenous artist of some repute, Don Ningewance, who is also a “painter of light.” I purchased this painting of his at our Christmas market a few weeks ago for $800.

Whatever you might think of Ningewance’s somewhat cartoonish style and garish colours, the light effects are terrific, and also, I might add, what it looks like sometimes when conditions are right and the winter sun is low in the sky. Some people live in little log cabins just like that, with stone chimneys. There are pines and open water where it’s moving, despite the cold. And yes, there are wolves.

Ningewance’s art is a lot like Kinkade’s, at least it is at this stage of his career. It is idealistic and fantastical with its saturated colours and extreme lighting.

To sum up, briefly, we see in Wyeth, Rockwell and Kinkade some of the typical features of what may be considered to be conservative art, namely:

realism - recognizable figures and landscapes painted without distortion or exaggeration

virtue - whether it is Wyeth’s focus on the local people and places he knew, Rockwell’s focus on the clichés of Americana like the diner, the newsboy or the local citizen standing up for what’s right, or Kinkade’s idealistic and romantic forest cabin scenes, the art speaks to kinds of virtue: everyday, authenticity, honesty, humility, honour, trustworthiness.

tradition - For all three artists, though their techniques differ from austere (Wyeth) to familiar (Rockwell) to fantastical (Kinkade), all are masters of realist technique, which speaks to diligence, training, skill, acceptance of the authority of the past.

accessibility - All three artists also share an interest in meeting people where they live. Their pictures of everyday people and everyday places don’t talk down to you. They don’t pretend to be smarter than you. Whether you consider this to be popular or populist depends on where you are coming from. If you are conservative, popularity is not a bad thing; it’s socially cohesive in fact. But for the lefty liberal crowd, the same thing might be called populist, pushing it into alignment with right-wing ideology (fascist or fascist adjacent), which also serves to put those folkx ahead (more progressive) or above (more righteous). Using the term populist now is less a descriptive political term and more a rhetorical device indicating one’s status; it’s a form of virtue signalling, “Oh, we’re not like them.”

I have to stop now. This post is getting too long.

I’m going to continue with Part 3B tomorrow, when I’ll look at some more contemporary - as in modern (of the moment or at least the last 50 years, and museum brand) - art. I’m thinking about American artists John McNaughton, Charles Ray and John Currin, and Canadian artist Eldon Garnet in case you want to look them up. Possibly a couple of others.

In Part 3B - Some contemporary art is called “conservative” by critics because it does not sit comfortably within the canon of contemporaneity. Is such art called “conservative” because it doesn’t fit in, or does the work have some distinctive qualities that could help us define a conservative aesthetic?

Ta for now.

Please note: There will be a special post on Jan. 20th, in step with the Inauguration, in which I will be offering some coping tips for the liberal press. They are going to have a bumpy four years.

About this series

This post is Part 3A of a series on conservative aesthetics. The premise of the series is that the left owns culture, and the right, if it hopes to govern the whole of the people, or to grow its base, needs to find its way into the discourses of culture, which means engaging with, and contributing to art theory, art criticism and creativity.

These are the posts in the series to date, with links:

Part 1 What's Wrong with the Right: The right is unfunny and culturally retarded. - There’s a lot of work to do obviously.

Part 2 Conservative Eye for the Woke Guy: Tie a Hermès scarf over that man bun, we're going for a ride, up town! - What are the aesthetics associated with conservatism; A look at a contemporary art star from a conservative point of view; Some observations on the arbitrariness of right/left when it comes to culture.

These are future posts in the works:

Part 4 The Power of Form - What is aesthetic “form?” What kinds of form does conservative art tend toward? And specifically, are there special forms that convey the idea of power separate from right or alt-right ideology.

Somewhere in here there will be a post about the movie The Brutalist, releasing in Canada on January 24th, 2025. Very timely and bound to sweep the Oscars (my prediction:).

Part 5 Funny Business - Why the right (and capitalism) have no sense of humour and what can be done about it.

Part 6 Ways of Seeing Right - How to critically assess art from a conservative point of view; where the left got art wrong.

A Patient as Art: Andrew Wyeth's Portrayal of Christina Olson's Neurologic Disorder in Christina's World - Marc C Patterson, Thomas B Cole, Eliot Siegel, Philip A Mackowiak.