Part 2 - Conservative Eye for the Woke Guy

Tie a Hermès scarf over that man bun, we're going for a ride, up town!

I began this series with this post about how the right gets culture wrong because that’s an obstacle to people like me, disenchanted lefties, getting fully on board with conservatism.1 Figuring out what conservatism is missing when it comes to culture is important because the left owns culture. From Hollywood to hand me downs, the heart is always on the sleeve. And they’ve gone nuts.

In this post, I’ll look at how the right looks at visual art specifically and at the end suggest a different approach that might be more productive for all concerned. The post is long, so buckle up. If you want to skip ahead, I’ve sectioned it off:

1. The basics of conservative culture

2. Aaron Renn’s four aesthetic styles of the right

3. An exercise in alternate art criticism: Jeff Koons

4. My corny Kumbaya conclusion

1. The basics of conservative culture

Conservatism is generally associated with convention: historically tried and true ways of doing things and standards of achievement. In terms of culture, the “classics” in any cultural category are preferred, whether it’s music (classical), dance (ballet), theatre (opera), architecture (neo-classical) or the visual arts (Old Masters, Impressionism). Anything new, out of the ordinary, or avant garde, not so much.2

Two or three artists come immediately to mind when we think about visual art and conservatism, artists like Andrew Wyeth, Norman Rockwell, Thomas Kinkade. I’ll look at these artists and few other artists another time, but first, let’s get a sense of what conservatism in taste means.

Conservatism at The New Yorker

You wouldn’t know it to read it these days, but The New Yorker used to be a bastion of American conservatism. To me anyway (Wikipedia disagrees). The full page ads for Tiffany’s3 and small ads for exquisitely crafted brooches and mission-style foyer tables told you the mag was speaking to monied people with taste. And if those folks aren’t conservative, then who is? (We’ll come back to this.)4

I always found The New Yorker to be very catholic in its coverage of the arts; if it was playing in New York, it was worth having a look or at least a listing. Personally, it was the cartoons and illustrations that drew me in. Reading was a slog but the writing was without fail superlative. Each art discipline had its own critic. Visual art-wise, critic Peter Schjeldahl ruled the roost at the New Yorker for decades. (He died in 2022.) I found his reviews quirky and off putting: “Cézanne doesn’t cut it.” he once pronounced. It must have been as much to shock as anything because Cézanne most definitely cuts it, and he knew that very well. Only an upper West Side New Yawker would have the audacity.

I’d venture to say nobody read Schjeldahl to see who was making it and who wasn’t. He tended to review the A list, the big shows, so nothing like that to do there. And there were trade journals for that, Art in America or Artforum. But, and this was perhaps the marker of New Yorker-ness back in the day, Schjeldahl’s writing was very good, classy New Yorker style and he always had something interesting to say. That’s good in a conservative sense: sensible, complex, decisive, but no preaching.5

Which is to say, there IS a conservative approach to culture, and the New Yorker used to be the best example of it, e.g. Schjeldahl. (Caveats6)

2. Aaron Renn’s four aesthetic styles of the right

Aaron Renn is a conservative Christian pundit. His substack at AaronRenn.com is thoughtful and informative and refreshingly “alternative.” I wholeheartedly recommend it if you want to know more about how conservatives view the world.

This particular Renn post sheds some light on conservatism from a cultural perspective. Renn is looking at people first, how groups of conservatives can be differentiated by their culture. That is not the same project as I’m engaged in here. I want to find in culture whether and how there are ideological, political differences. I feel it is too limiting to just take on the face of it what various conservatives identify with culturally. But let’s look at what Mr. Renn has to say.

Renn sees conservatives in four cultural groups:

Retro-Americanism, within which there are two types: “Traditional American aesthetics, often with a retro flair, appeals to educated conservative voters and donors, whereas neoclassical aesthetics with a fine arts sensibility is the de facto aesthetic system of movement conservative elites.” Renn understands this stream of conservative aesthetics to be firmly against “the modern,” anything contemporary or “out there,'“ which attitude he rightly considers to be an obstacle to innovation. Art depicting rustic Americana or neoclassical architecture are the primary exemplars of this aesthetic. Do we need an image here of a weathered barn and Amercian flag or a 1950s post office building?

Techno-futurism is the domain of Silicon Valley tech wizards who eschew culture, see themselves as a superior elite, and generally favour anything shiny, plastic or metal, with crisp edges. Think of Tesla’s Cybertruck. Note: Renn’s category has nothing to do with the historical avant garde art movement Futurism. Rather it has more affinity with science-fiction pulp novel covers, all space suits and antennae. Renn observes that this version of conservatism is non-conforming and considers itself “progressive,” noting, interestingly, that AI generated images (less shiny but still conspicuously artificial) are tending now to be associated with this breed of conservatism. For example:

Neofascism - Renn takes symbols of fascism like the Swastika or the Black Sun to be “an aesthetic,” and, I should note, very deliberately qualifies them as a very minor part of conservatism (the fanatical alt-right you might call it). He has little to say about them other than warning people to stay away. While that is of course good advice, I think such symbols alone do not constitute an aesthetic, as in a distinctive style or movement. As I have suggested in this post, I believe there is such a thing as a fascist aesthetic or what we might call an aesthetic of power that can be separated from fascist ideology. Whether or not one worked for Hitler is not the determining factor. One particularly powerful photograph by the American photographer, Paul Strand, comes to mind. Another post in this series will explore this particular subject.

MAGAism - This Renn category is a catch all for anything regular folk are into. It has no elite supervision, no experts and few if any distinguishing features. It is often kitchy, garish and boorish. Renn helpfully points out this is not a economic class phenomenon, but a social one. Where I live, there are a lot of trucks, quads (all terrain vehicles or ATVs), snowmobiles, and an outdoorsy culture of fishing and hunting. You see a lot of camo, baseball caps, denim, safety vests and steel toed boots. I would not venture to say how my neighbours vote. I don’t know and I don’t particularly care. People live in a “populist” way, average. While quotidian lifestyle of the average American or Canadian has little to say for itself, it is interesting to consider that what is popular - what appeals to the most number of people - does not carry cultural signification the way other aesthetics do, just as the term “populism” used in politics is unhelpful because it does not carry political meaning the same way that terms like liberal or conservative, left of right do . What is popular is not subject to gatekeepers, tastemakers. It is in a way non-hierarchical. Nothing is prohibitively expensive. Design style, materials and price are responsive to the marketplace rather than dictating to it. All of which makes it interesting, but not “cultural” in the way I’m thinking of culture, that is, as the intentional creation of experience through the application of intellect and emotion.

3. An exercise in alternate art criticism

Aaron Renn’s categories are helpful in looking at things around us in terms of political bent. But let’s cut to the chase, get to the fun stuff: capital “A” Art; not the clichéd, sentimental retro-realism or techno-futurism that typically is identified with conservatism, but real art, the stuff that thousands of educated, sensitive, interested people have, over thousand of years, developed a consensus about.

My thesis is that you should be able take any artwork from any period and find in it, or ascribe to it, conservative values. Conservatives just have never wanted to or had to do it. It’s time to change that.

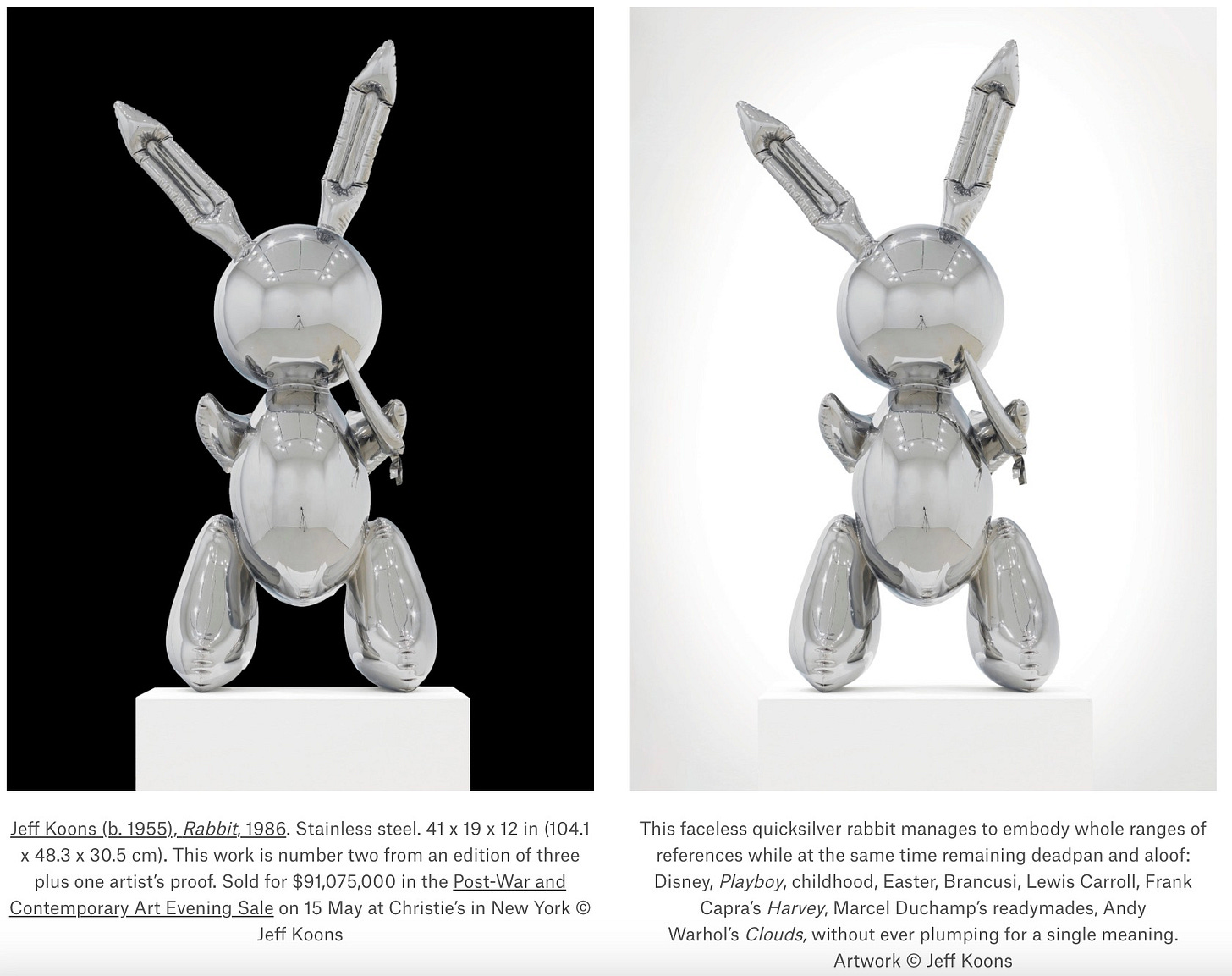

Let’s take an easy example that is pretty contemporary, and certainly famous, still holding the record for the highest price paid at auction for any work by a living artist.

Jeff Koons’ Rabbit

Jeff Koons came to prominence in the mid-1980s, which tells you something. The 80s was a plastic oasis contrived to disguise the fact that we were living in a cultural desert. After the efflorescence of the 60s and early 70s, there really was nothing left to be done in visual art. The account had been emptied. Nothing left but the crying, as I’m fond of saying.7

Read Koons bio on Wikipedia. It explains a lot about how he came to make the kind of art he makes; it’s all business from A to B and back again.8

I asked Google “Is Jeff Koons’ art conservative.” And it’s AI function answered (my responses in CAPS):

No, Jeff Koons' art is not considered conservative:

Subversive

Koons' art often pokes fun at suburban life and consumer culture. He uses unlikely subjects like children's toys and celebrities to criticize contemporary culture. FAIR ‘NUFF, SATIRE IS NOT GENERALLY WHAT CONSERVATIVES DO. TOO BUSY MAKING MONEY TO BE CLEVER.

Anti-establishment

Koons has antagonized the art world by questioning its authority on what is good and bad art. He has also been described as provocative and commercial. HMM, COMMERCIAL. ALSO, QUESTIONS THE PREVAILING ORTHODOXY CREATED BY ART GATEKEEPERS, THE CRITICS, CURATORS AND MUSEUMS. OK, LEANING RIGHT I’D SAY.

Post-Postmodern

Koons' work has moved from Postmodern anti-humanist art to a Post-Postmodern reintroduction of the human and reality into art. “HUMAN,” “REALITY,” DEFINITE MARKERS OF CONSERVATISM.

Democratic

Koons has expressed a desire to create art that is accessible to anyone. He claims to create art for the masses. BINGO, GO TO THE PEOPLE, THE PEOPLE KNOW BEST. ENTREPRENEURIALISM 101.

CONCLUSION: GOOGLE AI IS WRONG (surprise), JEFF KOONS IS A CONSERVATIVE ARTIST.

I’m a little rusty in writing art criticism, but let’s consider Mr. Koons in relation to art critical discourse the way I was taught it.

Precedent: Everything in art (and in most disciplines actually) is meaningful in relation to what preceded it. There is no “new” without an “old.” The present builds on the past. The main precedent for Koons would be pop art. Instead of soup cans à la Warhol we have balloon animals à la Koons.

The next precedent would be Duchamp’s readymades (explained to the best of my limited abilities here in the section What is Avant Garde?). Koons doesn’t take an actual balloon animal and put it in a gallery because… because why? because we’re past Duchamp. So far past. We’re into post postmodernism now, neo post postmodernism, whatever.

Context: Every work of art gains meaning from its time and its surroundings. Artists don’t work in a vacuum but neither do they have to self-consciously strategize how #thisorthatmatters to be relevant.9

Koons was, in the 80s, working at a very difficult time for people who have imagination. The cupboard was bare; the previous generation did not restock the shelves. The trajectory of modernism, of ‘negative critique’ you might call it, had come to the end of the line. A lot of BS art was popping up everywhere: “new painting, performance art, installation art, text art, environmental art, political art,” all rehashing tired old tropes with a few novel twists. And no shortage of patrons. Art has long been an industry, and the hunger for “the new” is insatiable.

What’s a creative fella to do? How about ordering up a polished stainless steel replica of an inflated bunny rabbit?

Technique: I may be wrong but it looks to me like Koons never ever constructed any of his artwork himself. Everything is fabricated. He didn’t even try. If you read his bio, you will appreciate why. He was copying Old Masters for his pop’s furniture store at the age of 8. In any event, fabrication is de rigeur for artists today. It’s hard to avoid when you get into museum scale productions. And it’s reflective of where we are industrially as a society.

Art history: Rabbits and hares have been depicted in art for thousands of years. They are associated with fertility, innocence, mortality, rebirth, purity and helplessness. They figure large in art across the ages, from ancient Egypt, Grecian urns, Chinese tapestry, medieval manuscripts, Roman mosaics to new World Americana and contemporary art (see here, same article on The Last Avant Garde, a bunny wouldn’t you know).

I am speculating but it would not surprise me if Koons was inspired by this particularly fine art historical precedent, a watercolour drawing by Albrecht Durer from 1502.

So, is Jeff Koons a conservative artist?

Let’s put it this way: anybody who pays $91m for a work of art by a living artist can’t be considered a liberal, even if they choose to drop sackfuls of money into Democratic party super pacs. They may or may not care about Jeff Koons personal politics (or even whether he votes) but chances are they see in the work something that reflects their own values, industry and achievement. And, to my way of thinking, outlined above, Koons’ work has a lot of the markers of conservatism: it’s studied (historically relevant), very highly crafted and delightful to look at (beautiful), and flows effortlessly within the cultural stream of commodity capitalism (of its time).

But art criticism is more than precedent, context, history and technique. There is also interpretation, in the sense of meanings that we associate with the artwork or how we attach meaning to the work. This is the core of criticism and where conservatism is most wanting.10

Conservatism is a lot like men. They’d rather just not talk about it. So talking about culture, likes and dislikes, does not come naturally. - Me

What can we say about Jeff Koons’ Rabbit that is about more than its connection to art history, to the time it was made and its technique or craft? All of that is impeccable: the “polish” of the work, both literally its shininess, but also the perfection of the industrial craft behind it is remarkable. It’s connection to art history, fable and myth, is rich. And it is beautiful to look at, and cheeky. It’s smart, but not pretending to be smarter than you.11

But there is more to it than that. Even in 1986, it was a provocative act to bring a balloon rabbit (no matter how well made) into the pristine, privileged space of the art gallery. It sent critics into paroxysms, effusive praise on one hand (the left) and utter contempt on the other (the right).

The same conservative journal, The New Criterion, that pilloried New Yorker art critic Peter Schjeldahl as a flakey lefty fashionista, castigated New York Times critic Roberta Smith for praising the work, calling Rabbit “an insult to the standards of Western art going back to Giotto” (14th C).12

In this critique, we see the knee-jerk behaviour pattern of conservatism: appeal to the past, resist change, all at the expense of thoughtful consideration. Towards the end of Pat Lipsky’s rant against Smith and Koons, he calls Rabbit “an emblem of wealth.” One would think that a work of art so conspicuously related to capitalism would spark more careful examination by a conservative.

There are things about Rabbit that let us understand it as a critique of capitalism: Frederic Jameson, a leading theorist of the critique of capitalism postulated that the signs of the end of capitalism (a.k.a. late capitalism) include: "crisis of historicity", a "waning of affect", and a prevalence of pastiche. (Affect means feelings. Pastiche means imitation of different styles mixed together.)

It would be easy to see those three signs of “the end of capitalism” in Koons’ Rabbit. In its mechanical, robotic perfection it is futuristic (breaks with history), metallic (emotionally cold), and a pastiche (a melange) of art influences, from Durer to Duchamp as previously noted.

But could we not equally, and oppositely say that historically Koon’s Rabbit is in a long line of portrayals of rabbits as they have interested people since the beginning of rabbits and people? And that far from being cold, as a sculpture sitting in your living room (not that it ever in your wildest dreams would be) Rabbit is charming, funny and eminently accessible, friendly even. And finally, as for pastiche, it is hardly that. Few artists, perhaps none at all, before Koons ventured to create such a perfectly crafted artwork in metal, or to adopt “balloon style” as a formal motif.

It is easy today in hindsight to imagine what a shock it would have been for The New Criterion critic to agree with Roberta Smith and the New York Times, staunch right/left enemies, that Koons’ Rabbit was not a work to be hated for its satirical commercialism, but a work of outstanding craftsmanship (worthy of Tiffany’s) in a fine historical lineage to be studied, enjoyed and cherished.

4. My corny Kumbaya conclusion

For conservatives to gain traction in the arts, they need to get into it in ways they have traditionally not wanted to or had to. It was enough in the past for someone like the heiress Peggy Guggenheim to use her family’s fortune to escape into a bohemian life, support avant garde artists, collect their work and eventually build a museum in New York. Conservatism back in those days tolerated all manner of diversity and weirdness and did not whine about it or carp about wasted money, perhaps because it felt immune from cultural sway, and, frankly, it could afford to.

Today that is simply not the case. Left and right are equally monied but not equally engaged across the social/cultural spectrum. The right needs to step up its game by participating in serious cultural work; theory, criticism and creation. I am confident that in the process, new hitherto unexplored territory will open up for discussion that might bring us all together across ideological or political lines.

In researching this essay, looking around for “conservative art” (there is precious little out there I’ll tell you), I came across an interesting anecdote about a fellow named Yosi Sergant.

Sergant is (or was for a time) a darling of the left. He is best known for commissioning Shepard Fairey’s “Hope” poster of Barack Obama during the 2008 presidential campaign. For his trouble, Sergent got a plumb position at the National Endowment for the Arts but ran into trouble when he held a hundred person teleconference with grant recipients at which he started to dictate what kind of work they were to support. He was run out of town (rightly so) and worked independently thereafter staging lefty liberal social justice art fests. More recently, he seems to have experienced, if not a change of heart, a little openness.

For a political convention called Politicon in 2016 he invited a self-professed conservative artist Julian Raven to exhibit a portrait of Donald Trump called “Unafraid and Unashamed.”13

“We don’t agree on issues,” Raven said at the time. “He’s hardcore liberal, but we have a respectful relationship.”

Sergant, for his part, said. “I, for one, believe we could use even more artistry in our discourse to challenge us to engage in a deeper and more creative conversation than politics often affords us.”

Yes, he really said that. Kumbaya my Lord, Kumbaya.

PS. About the illustrations in this post.14

The title of this piece refers to the TV series “Queer Eye for the Straight Guy” which appeared on Bravo in 2003 and was revived on Netflix in 2018 as “Queer Eye.” Now in its 9th season.

This is a very good synopsis of the parameters of conservative art on Quora by Inna Linnakova. (I’ve asked for the name of the artist who did the weird painting featured in the post.)

To be honest, I love advertising, especially high class advertising and the Tiffany blue is to die for. Tiffany & Co. is the Tiffany in the 60s classic movie Breakfast with Tiffany’s, which on the one hand, is now condemned to the dustbin along with all culture produced before 2021 due it’s representation of stereotypes, and on the other, has been rediscovered as a tale revealing women’s oppression and exploitation.

Not being “from money,” as they say, I was wondering how exactly I came to know about the New Yorker. At our house, we had Reader’s Digest and Life, maybe Chatelaine. I think it was through my best friend in high school who lived in a tiny bungalow down the street. Despite its outward modesty, the house was very tastefully appointed inside where my friend, built like a football player, lived with his similarly proportioned father and older brother, and his mom, a petit, pretty woman all of five feet tall. I’m pretty sure that’s where I saw my first copy of the New Yorker, on a coffee table…. My friend wanted to take up the guitar at one point, so he bought a guitar, a Martin. That kind of says it all.

Schjeldahl was passed over for a Pulitzer in 2021, jurors making two conspicuously affirmative action choices (one black, one gender “diversity” based) instead. That must have hurt. Since then, the New Yorker has been poisoned by wokeness, so fuck them.

This particularly venomous attack on Schjeldalh’s style of criticism concludes that he wrote about art like it was fashion. I couldn’t agree more but the point really is how is that a bad thing?

This posthumous review is more generous, capturing something of the magic of Schjeldahl’s writing: “dense, epigrammatic sentences, zany metaphors, and a chatty authority that was both deceptively approachable and disarmingly smart.”

However, what then are we to make of the fact that The New Yorker is known as a liberal magazine, including endorsing Democratic party candidates since about 2003? I can think of two explanations:

As I said earlier, the left owns culture and any magazine that is almost exclusively about literature, art, music and theatre is per force going to be considered left leaning. I would argue that this is a mistake. Political classification should be based on the nature of the writing on culture, not on the fact that it’s all just culture. But given the paucity of self-declared, or obviously conservative writing about culture, this is what happens; the left claims it.

I also think there are few, too few, substantial differences between the political poles under Western democracies, they just go about things differently, with different people who are just as cliquish, arrogant and corrupt as the other guys. Nobody really cares if The New Yorker is left or right. Until, that is, the magazine starts to wear its heart on its sleeve as it is increasingly doing now; stepping onto the slippery slope of wokeness. This is a real problem, especially now when everyone has become freakishly political, decrying the opposition as “evil” or “fascists.” There is no doubt much writing about this elsewhere. Enjoy. As for me, I see two profound issues that distinguish the parties at this moment, the undeniable enormity of the state apparatus and the proliferation of compassion propaganda. But enough of that for now.

Trust me, I was there: M.F.A. Nova Scotia College of Art & Design, 1985.

“A to B and back again” is the subtitle of a book of aphorisms and sayings attributed to Andy Warhol: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Philosophy_of_Andy_Warhol

I want to rant here: If an artist is any good (smart, imaginative and hard working), what they produce is going to reflect their reality as they experience it. What’s going on right now in art discourse discounts the experience of the artist in their time, and instead appropriates the object for the purposes of a current ideological agenda. Let’s grant for a moment that that is fine; it’s what young people do, reject the past while building something around themselves, but let’s not confuse that with art criticism or art history. Also whatever young people think they are doing, it is without question a form of colonialism. Crazy eh?

Another faint voice in the wilderness of conservatism calls for conservatives to get involved and start talking about art: “Such a conservatism would not be shy about liking some things more than others and making prejudicial judgments about their worth on the basis of taste.” - D. T. Sheffler on Aesthetic Conservatism.

I am indebted here to my good friend, artist Al Rushton, for introducing me to the idea of artworks having personality. While art criticism often considers the effect an artwork may have on its audience, including whether it evokes particular emotion (affect), Rushton uniquely regards artworks like people you meet and interact with. Thus, some art might be dumbed down, insulting your intelligence, some might be congenial (easy to get along with), some might put on airs, alluding to the rarified atmosphere of intellectualism or preaching with moral self-righteousness.

I drew the three pencil sketches illustrating this post. The satirical idea of “spot the fascist” arose after writing about how the term fascism is be misused all around us. The drawings ask, Is this what we are turning into, finger pointers, gossips and spies?