N. B. This post is a review of David Mamet’s movie Henry Johnson. How it fits into my series, On Conservative Aesthetics, is explained toward the end.

Playwright, author, movie director and producer, poet and cartoonist, David Mamet writes dialogue. That’s what he’s good at. So good and so unique, in fact, that the term “Mametesque” has been coined to describe imitators.

Dialogue is what makes plays. Movies too, but less so. Plays are just text to begin with; they can be read. Movies not so much. Movies are more… something… situational maybe, plus action, a lot of action generally: car chases, fast cuts, bedroom scenes, eerie music, stunts. Before a movie starts shooting it is storyboarded, sketched out scene by scene. Nobody does that with plays.

Henry Johnson is a movie based on a play, and it is also very play-like. Very little happens in the movie. There are only three sets, all interiors, and few camera angles in each. There are only two characters in each scene, and all they do is talk to (or possibly at) each other.

Henry Johnson — Synopsis

In the first scene — a traditionally appointed law office — a handsome young lawyer is shown to have been very gullible, and his gullibility has got him into serious trouble.

In the second scene — a jail cell (the young lawyer was in way more trouble than we thought) — he is subjected to the intimidating, convoluted and cynical worldview of his new cellmate, who may be protecting or preying on him. We can’t tell.

The third scene — the prison library — is in two parts. First, the young lawyer is exposed to more perplexing, confrontational tale-telling by his cellmate. Jump cut to some months later, and the young lawyer has taken a prison guard hostage and barricaded himself in the prison library. The guard exploits the young lawyer’s gullibility for the fourth, and fatally, last time.

Curtain.

The Allegory

People who are gullible will, and perhaps should be, treated harshly… or… Words don’t kill people, people kill people.

If the purpose of art is to reflect reality in critically interesting ways (debatable), David Mamet has produced a frighteningly good portrait of our times, times in which discourse has been weaponized with epithets, in which bleeding hearts when they are not choking themselves to death by the noose of good intentions, are making everybody else want to choke them with their self-righteousness.

The dialogue is staccato and aggressive (“Mametesque”), sometimes hard to follow (subtitles recommended). The movie is dark and sincere, like a Caravaggio painting. The characters are complex yet shown in stark contrast, highly realistic, without embellishment. It is also short (80 mins) and has been described as efficient.

The play fascinates in part because so much of the “action” is off stage, implied by the dialogue alone. There is no need to act out the young lawyers early seduction by a street smart fellow student, when it is revealed through the faux casual cross-examination by his mentor, a senior lawyer in the law firm he works for, or his fears of rape in prison encapsulated in a perverted re-telling of the story of Snow White/Sleeping Beauty by his cellmate, or the liaison he has with his prison therapist that he is persuaded to exploit by his cell-mate.

Snippets

Below are two pieces of the quite difficult dialogue for which Mamet is so celebrated. The first is when he meets his cellmate; a fairytale is his introduction to prison. This sets us up for the second, which twists the meaning of an affair our hero has with his prison therapist.

[The young lawyer, Henry, is sitting in his jail cell, fidgeting somewhat nervously, unpacking toiletries, when his cellmate, Gene, enters. They chat a bit, Gene sizing Henry up. Gene says it’s normal to be afraid you are going to get raped in jail, then launches into this:]

Gene: You know about Snow White? Let me tell you about Snow White. Sleeping Beauty? Oh yeah. Right? She’s so lovely, right? So assured someone’s going to rescue her because she knows what she’s got. Between her legs. And he takes her and he realizes, Fuck! Half the human race has one of these. Why did I just fight through thorns to get to her? Then the story ends. Happily ever after, meaning you don’t really want to know. See, half, or as you realize, all the human race has something between their legs that can be taken. Write it on a sheet of paper. Sleeping beauty, this girl. Somebody put her in a magic castle, put a spell on her? No. The spell was on her. Fairytale ogre just took advantage. See, that’s called ignorance. Okay, now comes the handsome prince. Here he is. First fellow she’s seen since she’s been locked up. They get married, but if the story continues. Oh. If the story continues, what does she do? She’s only known two people in her life. The one who got her jammed up and the one who came to break her free. So what’s the punch line?

Henry: I don’t know.

Gene: It’s the same man. Right? It has to be. There’s nobody else in the story. This monster, he comes back to see if her imprisonment has improved her mood you see. Is she ready to enjoy her slavery and bend over, and so forth? This man, good enough to put on a different outfit to see if she’s ready, you know? If she’s ready to bend over and so forth. This monster, kind enough to put on a different outfit, comes back to see if he can have her again after she’s learned her lesson.

Henry: Which is?

Gene: To lay back, look at the ceiling and figure it out. And she does. She figures it out. That’s why the story ends. When she got wise, she called the story off.

This tortured interpretation of two classic fables serves at least two purposes. The psycho-sexual babble skewers the kind of critical theory that finds colonialism everywhere, turning leadership into oppression, desire into perversity and discourse into manipulation. And it sets Gene up as the saviour of Henry, the beauty, without whom poor Henry will have no alternative but to “lay back and look at the ceiling.”

The fact that Gene is so obviously manipulative reminded me of this very excellent, also exasperating, New Yorker cartoon by Paul Noth from 20161 showing that the con can itself be part of the con.

[The cell scene cuts to the library where Gene has arranged for Henry to work, presumably saving him from the yard where he would have been “eaten alive.” Gene is interrogating Henry about an affair Henry has initiated with his prison therapist.]

Gene: See, I think she wants to join you in some, like a conjunction. You’re so much alike. You both don’t belong here. But here you both are. Mustn’t that mean something? Find her handsome prince in this shithole? Sure. Isn’t all wisdom found in low places? Of course. Wouldn’t it be bravery for her to recognize it? She who is so overcome with pity for your betrayals. She just wants to reach out to you if you would open yourself. As she’s done. Spread your legs, she can pour goodness into you. You big victim.

Henry: All right.

Gene: But why does she cry? So you’ll cry. Yeah. Which means she’s done her job. She’s broken through to you. Her life isn’t a sham. See, I say, fuck her. Fuck that. Use her as she is using you.

Henry: No.

Gene: No? She’s not using you? Why did she tell you this shit now? I mean, you’re fucked over. You’re fucked up. You can’t think.

More parody of critical theory (the science of second-guesses) at work here. For Gene, everyone is always playing everyone else. Gene uses a combination of implied threats and disarmingly convoluted insights to gain Henry’s confidence so that he can play Henry in his own way.

It’s a house of mirrors in which the naive, well-meaning but ignorant Henry loses himself. The trouble with misguided do-gooding is that real people get hurt, including the do-gooder.

And your point is?

In this series On Conservative Aesthetics (index here) I have been working on the ideas that there is a conservative aesthetic that it would be helpful to understand, and that art and culture generally can be approached from a conservative perspective, which might serve as an antidote to left-liberal excess.

I would not say that David Mamet’s art is conservative. It is too grotesquely about difficult relationships and tragic human nature. It will do no good to dress the monster up in ideological finery of any stripe.

That said, Henry Johnson demonstrates how ideology can stick to art, claims it for its own and smother it with meanings that serve one cause or another. If it is the case that the left owns culture, perhaps that is only because it has bothered to claim it. Pretty clear though, that they are not coming for Mamet anytime soon.

Since Mamet declared himself to have been a “brain-dead liberal” in 2008, people are starting to look at his past work differently, as if it might have been conservative all along. That’s a mug’s game in my opinion. It will do no good to either aggrandize or tear down the artist’s work by affiliating with some political prejudice.

The reviews

Reviews of Henry Johnson are generally either fawning tributes to the legendary playwright or condemningly bad, e.g:

“But Mamet now seemed to be trying to take the leap into some stylized wordplay version of Cubism. Going forward, his plays became increasingly airless and cryptic and dogmatic. He was no longer capturing human nature. He was pinning it down like a butterfly and diagramming it.” - Owen Gleiberman in Variety: https://variety.com/2025/film/reviews/henry-johnson-review-david-mamet-shia-labeouf-2-1236384167/

Yet mentioning Cubism is great because it acknowledges that what Mamet is doing is more art than politics. But to then say that Mamet’s Cubism is airless, cryptic and dogmatic is like saying Cubism is dry and formulaic. It is, but that’s beside the point.

Mamet's “stylized… airless and cryptic and dogmatic” text is very much illustrative of where literary culture is at these days. This is a very difficult time for everyone, and there’s no point mincing words about it. Art to be true will be as tortured and difficult as our experience.

Next Up

Mamet invented his own acting method. It’s called Practical Aesthetics. In another post, I will look into it to see whether it can contribute to the idea of conservative aesthetics. It’s certain to be no-nonsense. Here’s Mamet on acting:

“What I’m looking for in an actor is the knowledge and the courage to stand still and say the stupid fucking words, because when one does that and one has talent what you get is greatness,” Mamet said. “That’s when the real individuality of the actor comes out. It’s not what they can do with the script or to the script, it’s can they say the stupid fucking words without manipulating them.” - Leo Adam Biga in American Theatre: https://www.americantheatre.org/2022/05/24/david-mamet-and-the-stupid-fing-words/

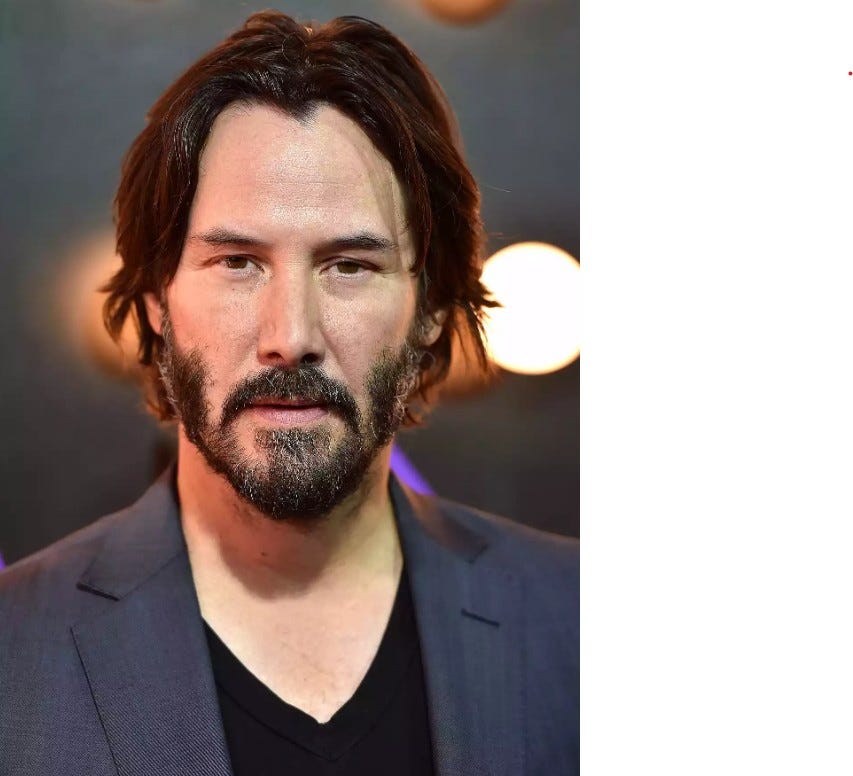

Makes me think of Keanu Reeves, an actor who just kind of puts his ego aside and lets the words speak for themselves.2

A la prochaine, mes amis.

image found here: https://www.cjr.org/q_and_a/new_yorker_cartoonist_trump.php