At this year’s Oscars, host Conan O’Brien interrupted his opening monologue to call attention to Adam Sandler who was sitting in the audience. Sandler was dressed unusually, in a baby blue hoodie and shorts. Conan mocked him for not dressing up the way everyone does for the event. Sandler feigned outrage, standing up and shouting about how he was being humiliated in front of his peers. He then made like he was so insulted he was going to leave but before going he looked around, asking “Where’s Chalamet?” Timothy Chalamet, star of the Dylan biopic, A Complete Unknown, raised his hand. Sandler ran over and gave him a big hug, yelling, “I love this guy.”

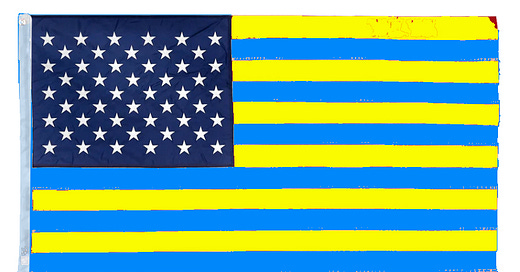

I didn’t get what was going on at all. People in the audience laughed but also seemed confused, but my sister got it right away. It was the colours, blue and yellow, Ukraine’s flag. The whole performance was a jab at the shameful behavior of Donald X and his minion JD Vance on the Friday before the awards, when they publicly humiliated Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

To complete the gag, Sandler invited the audience to join him at Veteran’s Park at midnight to play basketball, a sly and subtle reference to the military and perhaps the idea that we’d all be better off resolving our differences on the basketball court instead of the battlefield.

Sandler’s action was an allegory.

Wikipedia defines “allegory” as “a literary device or artistic form, a narrative or visual representation in which a character, place, or event can be interpreted to represent a meaning with moral or political significance.” Allegories are typically used to “convey (semi-) hidden or complex meanings through symbolic figures, actions, imagery, or events, which together create the moral, spiritual, or political meaning the author wishes to convey.”1

Allegories convey multiple, layered, complex messages. There is the literal message, which in this case was a parody of the haute couture or stuffiness of formal awards ceremonies. And then there were other messages: two Hollywood actors coming together to make the colours symbolizing Ukraine; the expression of support, “I love this guy;” and Sandler’s feigned “humiliation,” parodying the scandalous behaviour of Trump and Vance.

It is important, I think, to recognize Conan O’Brien’s part in this too. He triggered the performance by calling attention to Sandler’s get-up. It was not an accident or spontaneous action, but a staged political act. (It would be interesting to know if the plan was vetted by the show’s owner, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, or its executive producers, Raj Kapoor and Katy Mullan.)

The protest was an important correction to the media spin given to Friday's embarrassment. The Whitehouse spun it as all Zelenskyy’s fault as if he had insulted the President and Vice-President, and even America. The media fell in line with this interpretation. But Zelenskyy did nothing of the sort. He was polite throughout. He never raised his voice. He was in no way threatening or belittling. Rather, let’s be clear, he was being bullied into “signing” a preposterous “deal,” that would have given the US unprecedented access to Ukraine’s resources in return for nothing (payment for past or future support against Russia remaining undiscussed).

I put the words “signing,” “deal” and “payment” in quotations here because they are meaningless terms to Donald X. Time and again he has shown his word to be worthless. He has no respect for contracts, even ones that he himself signed.

Here he is smugly signing the Canada US Mexico Agreement in 2018, which he now says was “a very, very bad deal” for the US, begging the question Whose deal was it? Pretty much everyone recognizes the CUSMA overwhelmingly favoured the US and royally screwed Canada and Mexico who could not to manage to stand together to defend themselves. (Read about the agreement, its predecessor and current status here.)

Why allegory?

There is a tradition of actors and directors using their 60 seconds on the Oscar stage to champion particular causes. Though well-meaning, the messages are often naively based on black and white populist formulations of issues, and in effect, seem to be as much about vanity (virtue signalling) as they are about inspiring change.

In the past, such heartfelt demonstrations have had no consequence for the actors, who stand allegorically as avatars for “freedom of speech.” But today, celebrities would face cancellation if they dared to diss the political doctrine favoured by the audience. Nobody dares speak out against identity politics, for example, which has led to the suppression of free speech on university campuses, bias in academic and scientific research, publishing and so on. If one were to be against such things, one would be wise to keep it under wraps.

Donald X is also notoriously vindictive, lashing out against anyone who dares criticize. People are afraid to speak out. The term “kissing the ring” is becoming common when referring to statesmen and dignitaries who gain audience.

In such a climate, where there is a risk of retaliation, it is wise to make your critique less obvious. Sandler succeeded in doing so judging from the news reports and chatter on the socials. Nobody has called the performance what it was: a demonstration of solidarity with Ukraine and a bold critique of the appalling behaviour of the President and Vice-President.

We can expect to see more allegory in art.

Many people are lamenting the impoverished state of critical discourse in the arts today. Politics is unquestionably to blame. In this tortured state, artists are likely to start hiding their meanings if not their persons.

Since about 2010 it has been de rigueur for artists to align themselves with causes. Failure to do so has been perceived as reactionary, that is, not critical, not measured but just stubbornly resistant to change, aggressively against progressivism. Speaking one’s mind creatively, warts and all, risks being shunned by galleries and museums, being fired or hounded out of teaching positions, or personal cancellation.

There are two aspects to this failure of contemporary art: boredom and repression.

The banality of so-called progressive art is being noticed. Here is a quote from The Painted Protest, an essay in Harper’s Magazine by Dean Kissik reviewing a particular art exhibition titled Unravel:

“While Unravel pretended to be politically radical—even revolutionary—it didn’t seem to stand for much beyond liberal orthodoxy and feel-good ambient diversity. It offered fantasies of resistance, but had little to offer in terms of genuine, substantive social change or artistic experimentation. The works were almost entirely produced with traditional methods and materials, in recognizable aesthetics, and might as well have dated from half a century ago, if not much earlier.”

The stifling of free expression by political correctness is also being noticed. The German artist, Hito Steyerl, in this article in the German publication Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ), decries the unfreedom of art due to politicization:

“Art is replaced by ‘art’ scandals. The advantage: every bureaucrat and commissioner can play along; Form is suffocated by content.”

In a previous article:

“The current international art world is a jumble of different zones in which art is massively instrumentalized for political purposes. … The twenty-year period in which contemporary art was understood as the hip lingua franca of a globalized cultural elite is over. It marks the end not only of a certain epoch of “world art”, but also of the outstanding role of the visual arts as an expression of the present.”

Not so long ago, “political” art was a minor, unusual but sometimes important, thing in the visual arts. Occasionally artists would take up a cause and do some work “about it.” People would take note. Some artists also became converts to ideology, Marxism in particular, and would take up making didactic art, that is, art with an overt message, content-heavy to make its political point, often (perhaps necessarily) at the expense of craft, talent or concept.

I liked didactic art and even did some in my time. It takes up the project of educating, not as an antidote to, but in balance with the pleasure and interest of an artwork. It had its place and, one might say, knew its place as a form of resistance. Resistance, however, when it becomes dominant is no longer corrective; it is authoritarian, the very thing it most fears and criticizes.

PS

The next part of my series On Conservative Aesthetics is in the works, likely coming this weekend. To be honest, I am struggling with the very idea that some art is formally more “powerful” than other art and that such “power” would conveniently align with conservatism. In fact, I am doubting the whole premise of this series, that there is such a thing as conservative aesthetics.

I must add that the election this past Sunday of Mark Carney, former Governor of the Bank of Canada and of the Bank of England, to lead the Liberal Party of Canada into the next Canadian federal election has spun me around. I don’t quite know what to think. Much of my interest in conservatism stemmed from disgust with his predecessor.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allegory; The Tate is a very good source of general knowledge and definitions about the visual arts, for example, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/a/allegory