I had a disturbing encounter the other day on my morning run. My dog runs with me and often does her business enroute, as far away from the house as she can get. On this particular day, Doggie was trembling, mid-squat, when someone from some distance behind us shouted out that I should be using a poop bag. I turned; she was very agitated, pointing to a nearby dispenser.

Now I’m a city boy. I’ve had dogs and I’ve used poop bags a lot over the years. I don’t like the routine (who does?) but in the city, you do it for the greater good. City streets and dog parks would be disgusting otherwise.

However, where I live now is not the city. It’s about as far away from civilization as you can get by car. Our tiny community in the bush tries to look like a city with its signage: “Hotel District” ha ha ha, “bike paths” but just on new sections of road that abruptly end (wtf ?!?), even a roundabout, which is roundabout nuts. (Our mayor may be a visionary. Time will tell, I suppose.)

Up here in the boonies, in this rag tag agglomeration of buildings that has all the charm of a fuel dump, I have used poop bags on recreational trails followed by many people and many dogs. There is exactly one such trail. But where we were that day was not that trail. So I kept on running, which triggered Debby Dogooder’s self-righteous indignation response. She threw the proverbial fit, yelling and waving her arms about. That pissed me off. “Have the day you deserve,” she yelled in self-righteousness glee.

That was not a good solution. The poop was, rationally, materially, not a problem. It was nowhere near the trail, invisible, and would quickly be absorbed, with the added benefit of fertilizing pretty arid ground. But that was and is not the point. The point is I am a conflict avoider and all incidents of friction weigh heavily on me. Predictably, this ridiculous, trivial encounter has been bothering me for days.

Typically, this is how incidents like this play out in my head: First, I imagine all the things I might have said to explain why my action was justified. I was not going to, at that time and that place, pick up doggie’s doodoo. Then, I imagine all the clever things I could have said to the assailant to humiliate and shame them. And finally, my indignation settles on brute force. Just lay the bitch out, I thought.

There’s a term for this pathetic type of delayed reaction, coined by Diderot, “L’esprit de l’escalier,” roughly meaning, when you develop a response to whatever bad happened to you at the party (at the top of the stairs) only after you have left the party (at the bottom of the stairs on your way out).1

Been there. Done that. Like a million times.

Imaginary arguments

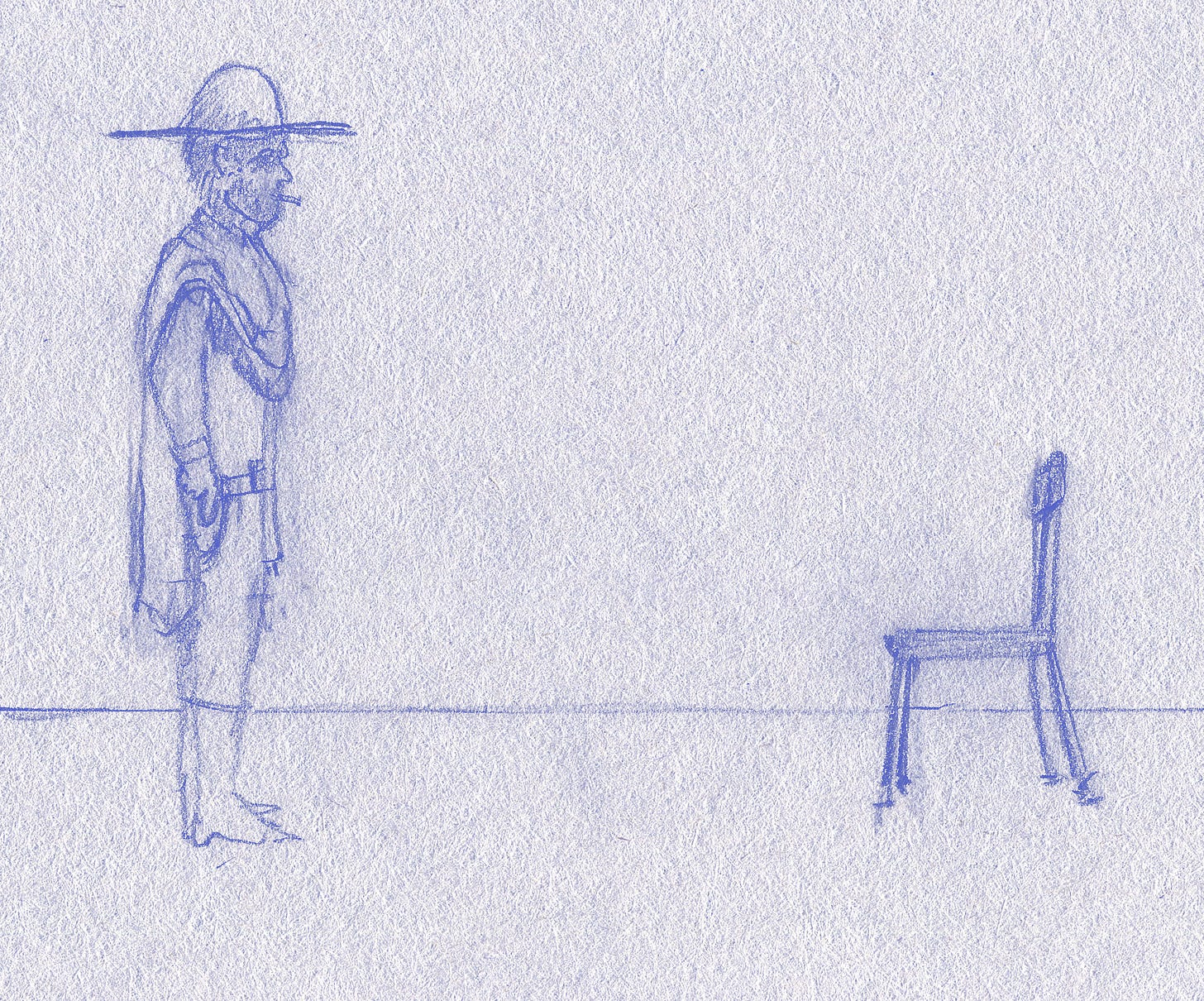

The incident reminded me of a renowned imaginary argument: when actor Clint Eastwood staged an argument with an imaginary Barack Obama (represented by an empty chair) on the stage of the Republican National Convention in 2012. (ref: Wikipedia)

Eastwood flopped. Everyone was embarrassed. He later apologized.

But I know just where he was coming from. We all do. You hear a politician or other authority blah blah blahing things you don’t agree with and you construct arguments back. “Oh yeah, well what about this… and this… and this, have you thought of that you son of a so and so?!?”

Such arguments always sound good in your head, but it’s hard to imagine them succeeding on any stage. The monologue that is only one side of an imagined dialogue would have to be very sophisticated, well-rehearsed and played before a knowing audience. And even then, in your head, the adversary is imagined. You hear their words, and you joust verbally with them. On stage, only half the story is being told.

Why do we bother at all with imaginary arguments? What purpose could they possibly serve? Perhaps some people are able to use the rant and rage in their heads to develop positions or stories, or scripts, people like David Mamet, for example, about whom I wrote recently, here.

It’s a mystery why so many of us persist in ranting and raving in our heads. It really does nothing more than reinforce our insecurities, our lack of self-esteem, our feelings of persecution and impotence. But it’s hard not to be triggered or to move past the conflict once you get submerged in it.

But the other side of it is there’s something exceptionally annoying about the type of people who feel entitled to police the rest of us mere mortals, as

captures so well in this note.2Ironically, I started running partly to deal with the civilizational malaise so many of us are suffering from, the polarization, the ranting. I’ve found it does get my brain working differently. I don’t know if it’s the exhaustion or what, but I’m better for it for sure.

Ironically, on that day, when I literally tried to run away from a problem, the opposite happened; it chased me around for days afterwards.

In the end was the beginning.

Would I have been much better off to have thanked the lady, apologized, got a poop bag from the dispenser, bagged the hot, stinking pile of shit, and dropped it in the also nearby garbage bin? I would have lost all of maybe 10 minutes of my run, and I could have then carried on, resentful about having been shamed into doing the right thing, but with a clear conscience.

But people like me, submissive conflict avoiders, are probably better off just giving in whenever things like this happen to me. Sure, I may carry the humiliation with me to the end of time, reliving the trauma in my head whenever I feel the need to pick on myself, but it is only me who will suffer and on some level, I will know that I did the right thing, if not to my way of thinking, then to someone else’s, someone more confident and capable, a smarter, stronger and better human being than I will ever be.

Diderot set forth this idea in an essay called The Paradox of the Actor (1830), according to this source: https://www.samwoolfe.com/2020/10/imaginary-arguments-with-people.html. The Paradox of the Actor is actually something adjacent to l’esprit de l’escalier. It was Diderot’s idea that actor’s should not try to feel the emotion of the characters they are playing but should simulate them, which then gave rise to “method acting” a la Stanislavski, (ref: Wikipedia) and the exact opposite of David Mamet’s school of “practical aesthetics”, which we like to call Action Acting. Mamet does not believe in actors interpreting the text. He wants them to get out of the way and let the words do the work. That is the writer’s craft.

“But the level of petty hostility and prigishness it would take to decide to … ruin a stranger’s day…as far as I’m concerned it's actually the height of evil. Because it's so pointless and petty … I truly hope that person … dies a slow death. … This is also how I feel about people who seemingly go online for no reason other than to spread their little pointless hostility comments to strangers.

About 10 years ago I realized that sometimes, while making a minor decision, I would preemptively have an argument in my head with some imagined adversary questioning my judgement. I suddenly realized that I can just make a decision — good or bad — without having to justify it to a phantom. And on the very unlikely chance someone asks why I did it, I can just say “I dunno, felt good in the moment.” This change in emotional valence has made my daily life lighter. Like, a lot.