50 ± 1 (repost with new illustrations)

Another take on passive consent and the managerial classes.

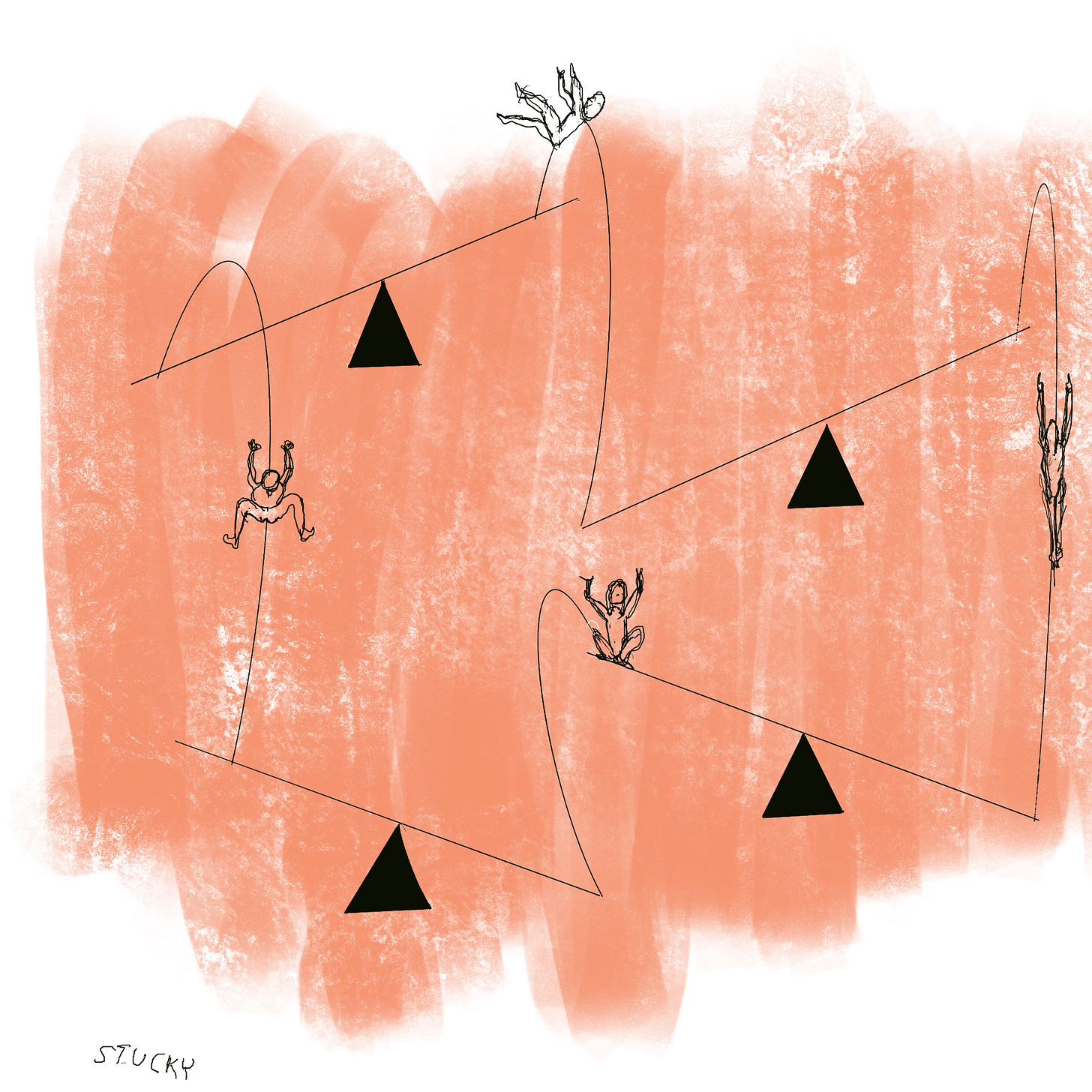

The illustrations I did for the last post were shite. Terrible. There’s an idea in there, though, something about balance, 50/50 ± 1, and how we, the people, are getting “played,” as they say, by mysterious forces beyond our control and quite beyond our ability to comprehend. So, die-hard that I am, I made some new illustrations. The text is a little different too towards the end. I’ve read the chapter of the book Hegemony Now on strategies as we advance for leftists, so there’s a paragraph about that at the end of this post. The original 50±1 post can be seen here if you’d like to compare.

Like you (most likely), I have been puzzled for at least a decade by the phenomenon of impossibly close elections—too close to call, with winners by the tiniest of margins, yet the stakes seem huge. How can the electorate be so evenly split? It’s mathematically virtually impossible that almost exactly half the people vote one way and half the other.

One explanation might be that there is little difference between political parties, so how people vote hardly matters. However, that is clearly not the case, at least not on the surface.

In their book Hegemony Now, Jeremy Gilbert and Alex Williams (Verso, 2022) give a very plausible, bigger-picture explanation: When we vote, we are in effect consenting to things we do not necessarily agree with or believe in. They call this phenomenon passive consent.

For folks on the right, Gilbert and Williams say, the feeling is that those purporting to represent our interests are the best we can hope for. For folks on the left, the idea of overturning capitalism is dead, and the feeling is similar; that the so-called “left” party is the best we can do.

This sad state of affairs does much to explain why the electorate appears to be so evenly divided. We aren’t actually that divided, we’re just not enthusiastic about either party. That’s what 50 ±1 looks like: indifference.

Gilbert and Williams have a lot of interesting things to say about how we got here and how we might make things better in the future. How we got here seems to have a lot to do with consumerism and the managerial classes. As long as most people have what they need and can enjoy consuming, no one is motivated to change the status quo. And to keep everyone rowing more or less in the same direction, we have hierarchies of professionals, semi-professionals and consultants to provide role models and mind the herd.

About the future

In their final chapter Gilbert and Williams drag out tired Marxist ideas about filling the proletariat with class consciousness, so they realize their oppression, and then become ripe for radicalization.

When the book came out in 2022, there was something called the Green New Deal, imagined by the authors to be the ultimate goal of political revolution: the idea being to align the whole world to save the planet. All the various identity politics groups would presumably have to abandon their petty bourgeois gender/sex infatuations to stand in solidarity against corporate intransigence on climate issues, thereby transforming passive, complicit government into an active force to globally enact and enforce carbon reduction.

It is almost comical now to read, in 2025, after the election of Donald Trump for a second term (a future by which the authors are no doubt horrified), their stated ambition to establish international socialism based on the democratic participation of the masses.

Not even socialist (the so-called Communist) countries like Russia and China are socialist anymore. Capitalism is everywhere. Perhaps the question we should be asking is whether people have agency, opportunity to be productive with a sense of purpose and the ability to self-actualize not only as consumers.

[This post was edited with the assistance of Grammarly.]

Next post will be about an experiment using AI.

Thanks for reading. Comments about the illustrations would be most welcome.